The persistent gap

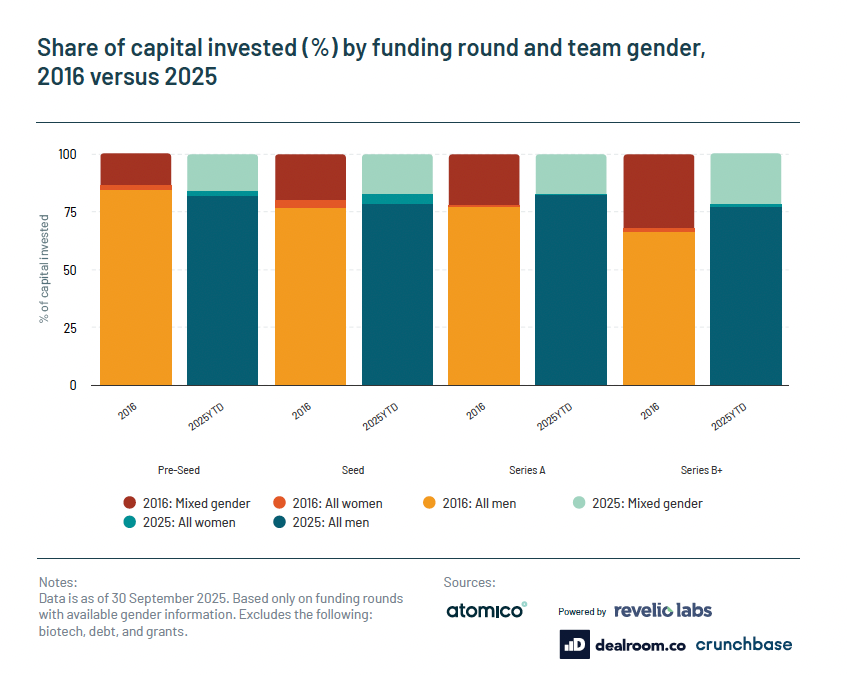

Female-founded and mixed-gender founding teams remain heavily underfunded compared to all-male teams across every VC funding stage in Europe. The gap is widening, not narrowing.

What the numbers show

Over the past twenty years, approximately 6% of European tech companies have been founded by all-women teams. This percentage has remained virtually unchanged since 2016.

These teams receive a disproportionately small share of VC capital at every investment stage. Even mixed-gender teams, which historically captured 32% of Series B funding in 2016, saw their share drop to 22% by 2025.

Out of the ten largest VC rounds in Europe in 2025, only one went to a mixed-gender founding team. The largest round for an all-female team did not make the top fifty rounds of the year.

Capital allocation by stage (2025)

| Funding Stage | All-women Teams | Mixed-gender Teams | All-male Teams |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Seed | ~6% | ~20% | ~74% |

| Seed | ~6% | ~20% | ~74% |

| Series A | ~6% | ~20% | ~74% |

| Series B | ~6% | 22% | 72% |

Source: Atomico State of European Tech 2025

All-male teams continue to capture the overwhelming majority of VC funding. Mixed-gender and all-women teams remain systematically underrepresented at every stage.

The structural nature of the problem

This is not a pipeline issue. The data shows consistent patterns across stages, and academic research reveals why these disparities persist despite equal or better performance.

Performance parity: Research demonstrates no significant performance differences based on the gender of entrepreneurs. Female-led ventures perform comparably to male-led ventures on objective metrics, yet female founders receive significantly less venture capital funding even after controlling for industry, geography, and business characteristics.

Evaluation bias: Early-stage investors consistently show preferences for pitches presented by male entrepreneurs compared with those presented by female entrepreneurs, even when the presented information is identical. This bias manifests in concrete ways during the evaluation process.

Question framing: When venture capitalists interact with entrepreneurs, they ask fundamentally different types of questions based on gender. Male entrepreneurs receive primarily promotion-focused questions about their ventures' potential gains and opportunities. Female entrepreneurs receive mainly prevention-focused questions about potential losses and risks. This asymmetry in questioning reflects and reinforces perceived risk differences that have no basis in actual venture performance.

Language of evaluation: The discourse used to evaluate entrepreneurs varies systematically by gender. When male entrepreneurs lack experience, this is often framed as "young and promising." Similar gaps in female entrepreneurs' experience are framed as "young and inexperienced." When female founders signal entrepreneurial traits such as assertiveness and risk-taking, they face disadvantage resulting in revised funding decisions due to higher perceived risk, creating a double bind where conforming to expected gender roles signals weakness while violating them signals risk.

Systemic coping mechanisms: The persistence and recognition of these biases has led to concerning practices, including 'venture bearding,' where women employ men as front persons in an attempt to lower perceived risk for male investors. The fact that such strategies exist and are discussed openly indicates both the severity and intractability of the problem.

Why the patterns persist

Multiple theoretical and empirical mechanisms explain the persistence of these biases:

Homophily effects: Venture capitalists tend to invest in entrepreneurs who share their demographic characteristics. Given that 93 percent of VCs are male, this creates systematic disadvantages in a male-dominated industry.

Role congruity: Leadership and scaling potential are associated with agentic traits such as assertiveness and risk-taking, which are culturally coded as masculine. This creates perception that female-led ventures carry higher risk, regardless of objective venture characteristics.

Pattern reinforcement: VCs develop mental models of successful entrepreneurs based on past experiences. Given that successful exits have historically involved predominantly male founders, these historical patterns influence current decision-making processes. The venture assessment process perpetuates existing patterns, as prior investment experiences reinforce the tendency to stick to established strategies.

Institutional variation: The gender gap is lower in larger and older venture capital firms with more formal evaluation systems in place. This suggests the problem is not inevitable but rather reflects specific organizational and decision-making structures that can be modified.

Investor-level dynamics

The disparity extends beyond entrepreneur evaluation to investor success patterns. Female venture capitalists do not benefit from the track record of their male colleagues in the same way that male investors show improved investment success in the presence of more successful colleagues. This differential is particularly significant in smaller firms.

Diverse teams, with women on board, lead to improved performance through more balanced decision-making, not only in ventures but also for venture capital firms themselves.

Market implications

The Atomico report describes this as a "vast set of companies remain critically underfunded." This language is precise. We are not discussing a small cohort or niche segment. We are discussing roughly one-quarter of the European tech founding population (combining all-women and mixed-gender teams) receiving single-digit to low double-digit percentages of available capital.

For investors focused on fundamental analysis rather than pattern-matching, this represents a systematic market inefficiency. When large segments of the market receive capital allocations potentially misaligned with business quality, pricing opportunities may emerge for disciplined buyers.

What has not changed

Policy discussions and ecosystem rhetoric have increased substantially over the past decade. Implementation and capital allocation have not kept pace.

The structural barriers remain intact. Female founders and gender-diverse teams continue to face significantly higher bars for capital access across identical ventures and comparable performance.

Bottom line

After twenty years of data, the pattern is clear and persistent. Female-founded and mixed-gender teams receive a fraction of VC funding relative to their numbers and performance.

This is not improving. Mixed-gender teams captured 32% of Series B funding in 2016. By 2025, that figure dropped to 22%. The trajectory is moving in the wrong direction.

For the European tech ecosystem, this represents a structural inefficiency in capital allocation that has persisted for two decades despite documented performance parity.

Sources: Atomico State of European Tech 2025; Brooks et al. (2014); Guzman & Kacperczyk (2019); Kanze et al. (2018); Malmström et al. (2020); Gompers et al. (2022); Calder-Wang & Gompers (2021); Ewens & Townsend (2020); Edwards & McGinley (2019); Franke et al. (2006); Eagly & Karau (2002)